Philosophers forever have contemplated just where the mind is and how the mind relates to both brain and body. Descartes, a French philosopher from the 17th century, was closely associated with an idea called dualism. This idea holds that the mind is non-physical – that it’s situated somewhere other than the brain or body. It’s not a substance – it’s in fact consciousness itself. He called this the mind-body problem. He said that mind can exist outside of the body and that the body cannot think. Mental phenomena are not physical. This gives birth the idea of soul – that there is a part of us that is not physical that exists beyond us

Rupert Sheldrake – a contemporary philosopher and man of faith says that our minds are part of a greater mind – that our minds exist outside of us and are part of something.

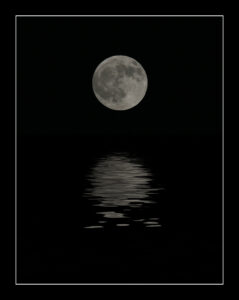

He used the analogy of a bucket of water reflecting the moon. The moon is clearly out there but it is also in a sense in the bucket. This is like our minds, he suggests. They are part of us – but they are also in other places. I don’t necessarily agree with this but it’s an interesting idea that has been with us for a long time.

With developments in neuroscience we can very much see that when the mind is active the brain is active. There is a contemporary argument that our mind is made up of nothing other than the physical brain, the chemicals, and the electrical impulses that take place.

Many think that as a consequence of new developments in neuroscience we can’t ignore the fact that many of our emotions and our responses are fuelled by chemical reactions in the brain. Think of nothing more than the fight or flight response that is driven by cortisol and adrenaline. When we’re stressed or scared, we become flooded with those chemicals and we respond to the presence of those chemicals by ‘fighting’ or ‘flighting’. This fuels a response in our sympathetic nervous system. We have another system called the parasympathetic nervous system which also has a little two-word analogy – the ‘rest and digest’ system or sometimes the ‘feed and breed’ system. Because when that system is activated we relax enough to take care of some of the other functions that our bodies needs to undertake in order to remain well. What we know is that if we are in a constant state of stress and if our sympathetic nervous system is dominant then our parasympathetic nervous system doesn’t get a look in. This, in many ways, is the ‘bio’ part of the biopsychosocial model.

I’d argue that as social workers we focus quite a bit on the social part of that model and to a significant extent on the psycho part of it, but we neglect the bio part. Emma Zara O’Brien in her book ‘Psychology, Human Growth and Development for Social Work’ (brilliant book – buy it!) says that the brain is arguably the foundation for, and core of, a person’s future development, behaviours, and experiences. She suggests that not being engaged with neuroscience or the biological underpinnings of human development reduces social workers ability to work alongside and with other professionals.

For many years it was believed that once we reached adulthood the brain was pretty much fixed. We know this now not to be true. The brain has a plasticity – an ability to change and develop. The brain reacts to changes in environment shaped by experience both positive and negative in children and in adults. Harari in his excellent book ‘Sapiens’ talks about this. He talks about our historic animal brain. I can relate this very much to how I see my dog ‘operate’. Essentially primitive brains work in two ways objectively and subjectively. So, my dog knows that if she runs into something it’s hard and it hurts. She knows that the world is full of smells and structures and she knows subjectively how she feels about them. She experiences excitement when she gets treats, she experiences fear if she doesn’t understand something, she experiences delight when having her tummy tickled. She understands the world in these simple objective and subjective ways. One of the problems for our human, developed, brain is that we have the capacity to move beyond objective and subjective understanding to know that there are things out there and feelings inside of us. But those feelings inside of us are still being driven by our primitive brain.

The amygdala the thing driving our fight or flight response is one of the oldest parts of our brain that we have and it’s not clever in the way it deals with things. It’s a one trick pony. It fuels us with adrenaline and cortisol. Humans have developed intellect and create stories about objective things and subjective experiences. We use everything we have to construct ideas of the world.

At birth our brain is 25% of its eventual adult weight. By a child’s second birthday the brain will have grown to 75% of its adult weight. This shows how much development of the brain is going on in the first 2 years of a child’s life as it explores its environment and experiences what’s going on around it. The change is rapid. The child is born with innate reflexes and as the brain develops the child develops ways to take control of these innate reflexes.

Our patterns of communicating are largely shaped by our early experiences from our primary caregivers. The brain needs a stimulating environment. If a child is severely neglected the brain does not develop normally. Sometimes pathways for language can be lost. The brains of children who’ve been denied stimulation can weigh less than the brains of children who have had such stimulation.

At around three years old the hippocampus matures, and this allows the retention of memories to begin – children have few memories before this time. Between the ages of 6 and 13 a growth spurt affects the brain regions concerned with language and spatial relationships. These changes improve thinking and social development and fuel abilities like being able to read, and social abilities like being able to make friends. Early experiences shape the people that we become.

Dr. Sunderland in the 2006 book The Signs of Parenting suggests the following. The developing brain in those crucial first years of childhood is highly vulnerable to stress. Many parenting techniques that are common can upset the delicate balance and stress response systems in the child. This can cause actual cell death in certain brain structures. Quality of life across the life course is dramatically affected by whether or not you established good stress regulating systems in your brain in childhood. One of the amygdala’s main functions is to work out the emotional meaning of everything that you experience. If the amygdala senses that something threatening is happening to you it communicates with another structure called the hypothalamus and this part of the brain actions the release of stress hormones which can prepare your body for fight or flight. Sunderland suggests that if you were left in childhood to manage your own painful feelings on your own your higher brain may not have developed the necessary wiring to be able to perform those wonderful stress managing functions. But all is not lost as the brain is malleable so talking therapies and other life experiences can mitigate against this. But, sadly, some people are left without this opportunity to transform.

The adult brain is fully mature at around 25 years of age. At this age and further into adulthood we have more thoughtful perceptions of the world around us (hopefully!) as the prefrontal cortex is fully developed and we can consider the consequences of our actions through reasoning. A lot of what I’m interested in in terms of self-care has implications here. Exercise promotes the development of brain derived neurotrophic factor. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), is a protein that stimulates the production of new brain cells and strengthens existing ones. When you release BDNF it helps grow brand new brain cells and pathways. High levels of BDNF makes you learn faster and remember better. BDNF also increases your brain’s plasticity – its ability to adapt. When you face stressful situations BDNF protects brain cells and helps them come back stronger. Exercise naturally raises levels of BDNF in your body. Cardiovascular exercise is best and, while a one-off session does no harm, BDNF increases more effectively with regular engagement in exercise. Your hippocampus, often referred to as the brake to your amygdala, shrinks as you get older and BDNF can maintain and even enlarge it.

When you rest (and meditate) you brains Default Mode Network is activated. This is a series of interconnected parts of the brain that get to work once we stop concentrating on external things – once we shift from outward focus to inward focused cognition. Interestingly people who rest effectively have more complex and better connected DMN’s. The complexity of our DMN shapes our capacity for self-awareness. Daniel Goleman says this leads to us being better pilots of our lives, helps us imagine our future, and gives us a greater ability to show empathy.

Our biology then has a significant impact on how, and maybe even ‘who’, we are. This begins to be shaped in our childhood and can continue to be shaped as adults. The impact is a direct consequence of environment, others, and self. We need to attend to all of these things for our personal wellbeing and, as social workers, need an awareness of these connections to help inform people of the potential for change and support people to facilitate such change to become those competent pilots of life.